At midnight this Monday, a group of employees from the Ratcliffe-on-Soar coal-fired power station (170 of the 3,000 who came to work at these facilities) were able to meet for the last time in the canteen of this county plant from Nottinghamshire, northern England. But this time they have come together to witness for streaming how the generating units of a plant that has provided energy for 57 years have been turned off. It was the last coal plant still active in the United Kingdom and thus puts an end to 142 years of relationship with this polluting fossil fuel, which is also the main generator of the carbon dioxide that overheats the planet.

This closes a fundamental chapter in the history of an island that was the protagonist of the Industrial Revolution, and that made coal its main economic engine and even the defining factor of its personality. The legendary London fog, long gone, was more the result of pollution caused by incessant combustion than by inclement weather.

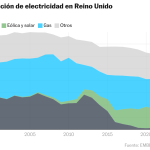

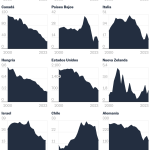

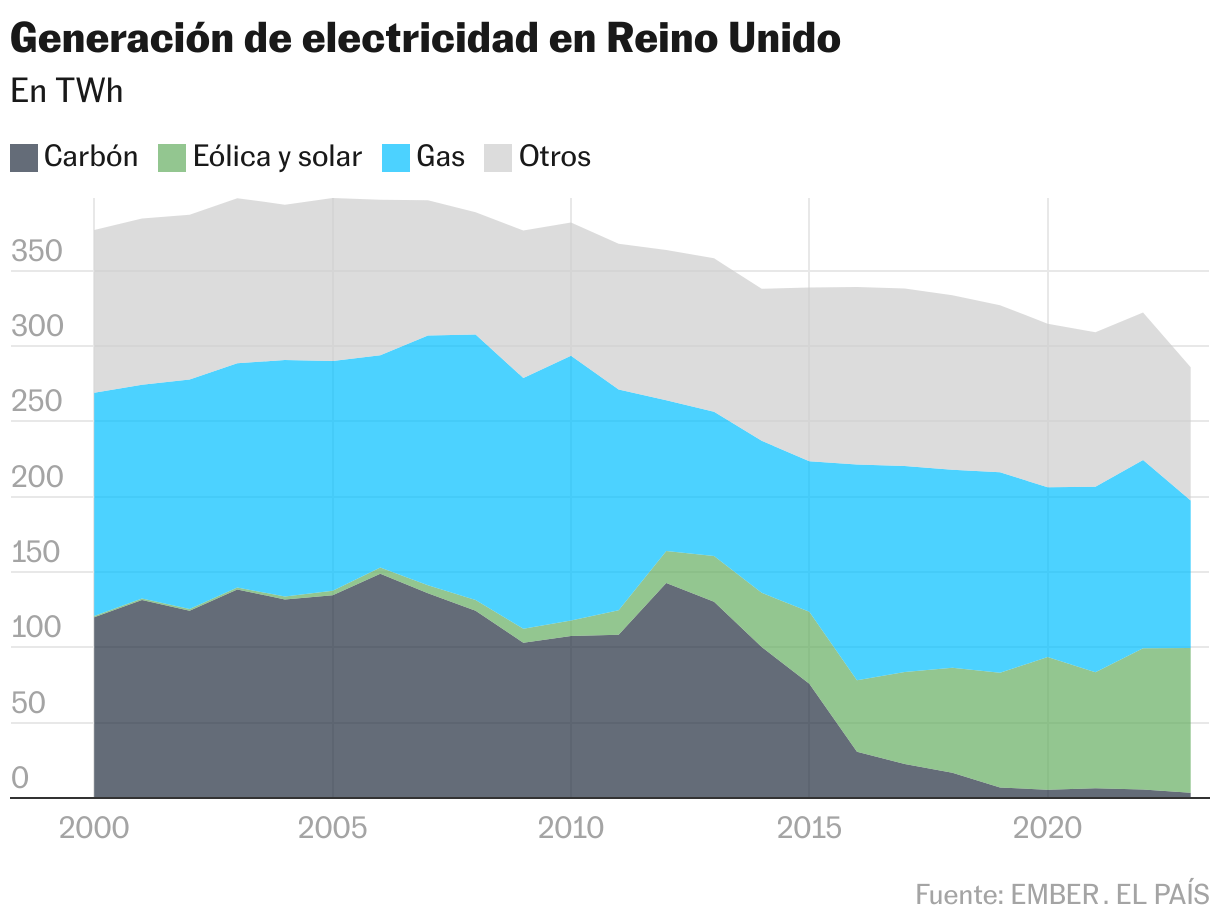

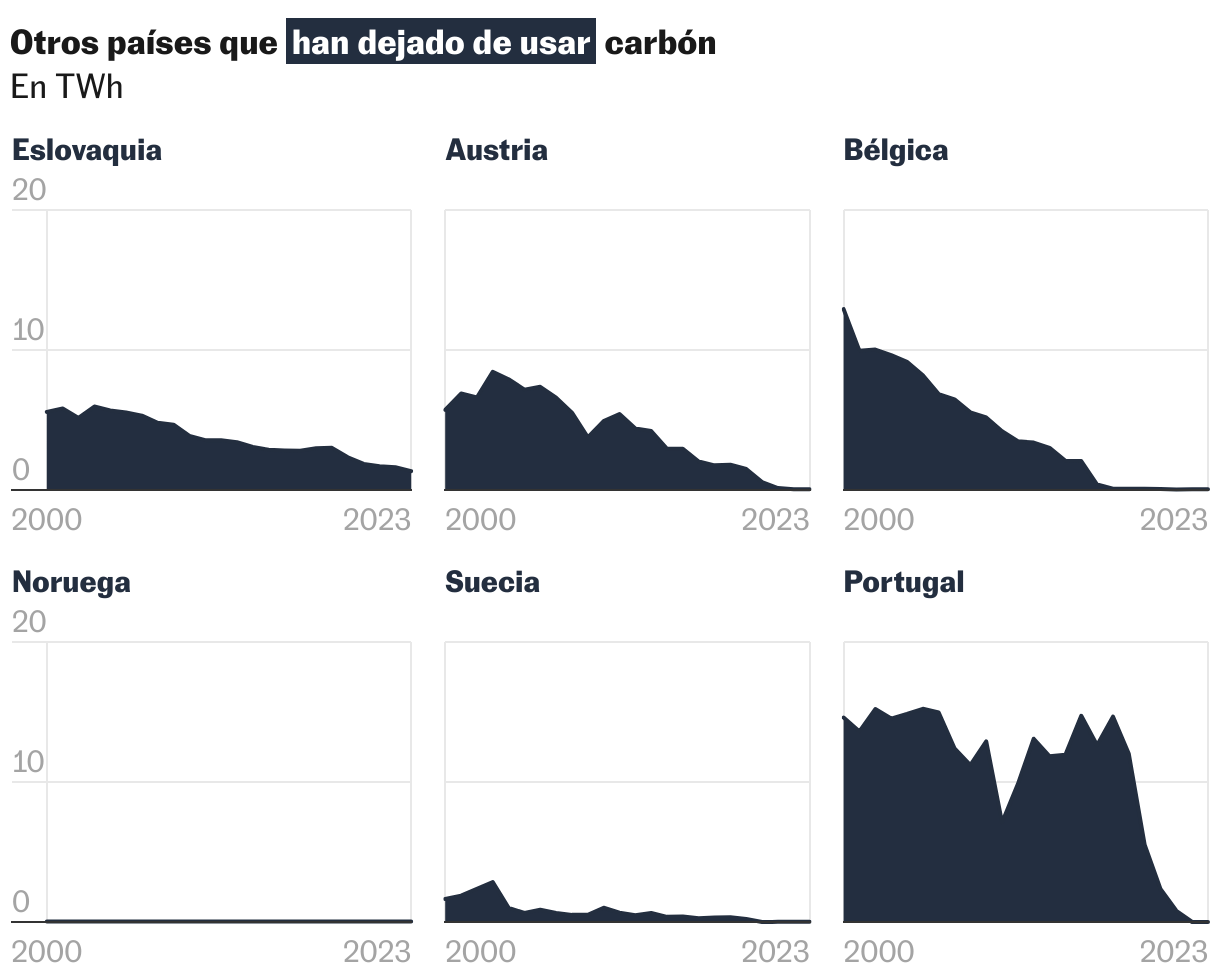

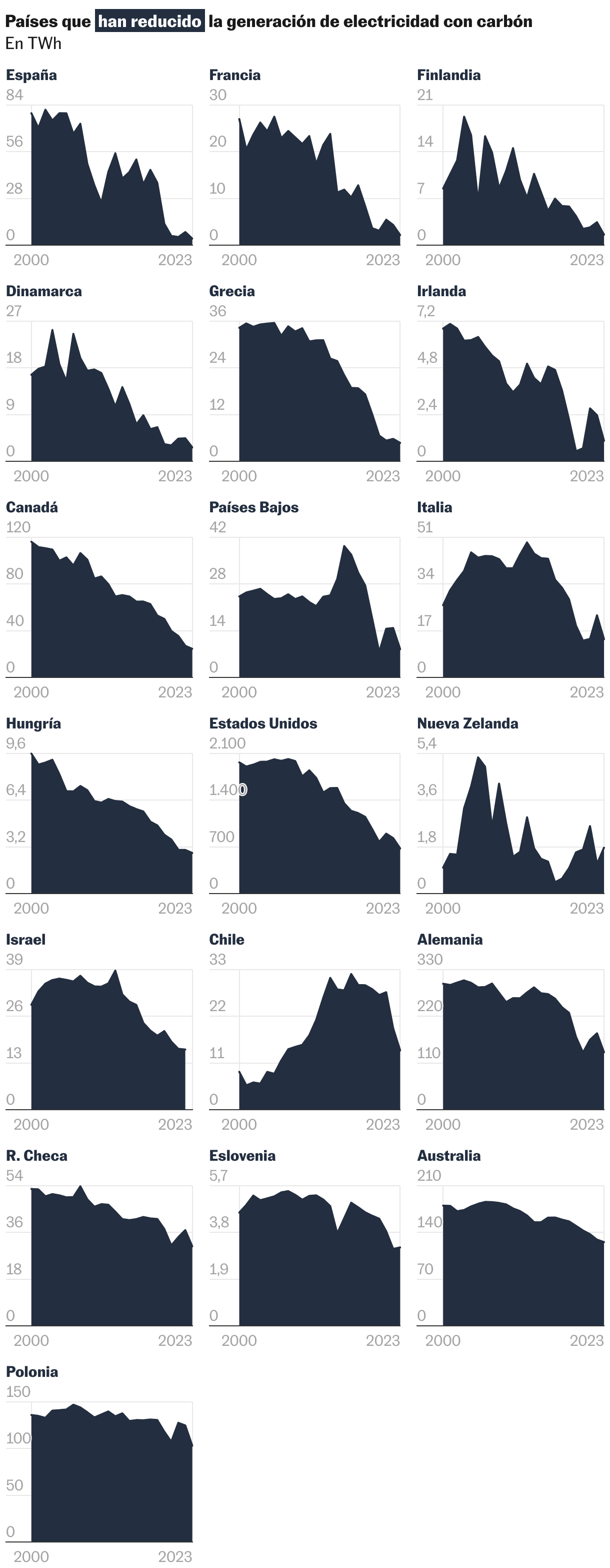

The first plant that burned coal to produce electricity in the United Kingdom began operating in 1882. And in the early nineties of the last century, 65% of the country’s electricity consumption was covered with this type of technology. But a mixture of loss of competitiveness with respect to gas and renewables and a set of climate policies sustained over time have led to an outcome that this Monday night was certified with the closure of Ratcliffe-on-Soar. The United Kingdom thus becomes the first G7 country to completely disengage from coal in its electricity sector. But it is not a rarity, because it is part of a trend to leave this fuel behind: a third of OECD countries no longer use coal, and three quarters are expected to have eliminated it by 2030. Spain, which has experienced a rapid disengagement process similar to that of the United Kingdom and where this technology already barely generates 1% of the electricity in the entire country, it has among its plans a total closure for next year. The concern of experts is now focused on some emerging countries (such as India, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines) where demand for this fuel continues to grow.

The first major decline in the use of coal in the United Kingdom occurred in the nineties of the last century due to the loss of competitiveness of the country’s mines and the increase in the use of gas. The second big drop was in the 2010s, when market reasons were joined by a package of measures against climate change from the Conservative Government headed by David Cameron. These measures, which were later also largely adopted by the European Union, were maintained over time with the different cabinets.

A report by energy and climate change think tank Ember outlines five key factors that facilitated this rapid weaning in the UK: announcing the end of coal by 2025 a decade in advance, putting a price on carbon dioxide, supporting energy offshore wind, reform the market to encourage renewables and invest in the grid to allow further development of clean alternatives. “The United Kingdom provided both carrots and sticks,” summarizes Phil MacDonald, CEO of Ember, about this policy that has combined incentives for cleaner energies and penalties for dirtier ones.

Discover the pulse of the planet in each news item, don’t miss anything.

KEEP READING

“The closure of Ratcliffe ends an era. Miners can be proud of a job that provided energy to the country for 140 years. Many generations of this country owe them a debt of gratitude,” said Michael Sanks, the British Secretary of State for Energy. This gradual elimination in the United Kingdom has allowed 880 million tons of carbon dioxide to be eliminated since 2012 (the equivalent of more than doubling the total emissions of the entire country’s economy in 2023). Furthermore, according to Ember’s calculations, replacing this fuel with wind and solar has resulted in savings of 2.9 billion pounds (about 3.475 million euros).

“The abandonment of coal by the United Kingdom is a tribute to all those who have fought against climate change over the last 20 years,” said Doug Parr, Policy Director of the organization Greenpeace UK. “There are still pending battles, such as suppressing the use of gas and oil,” he added.

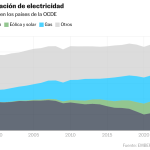

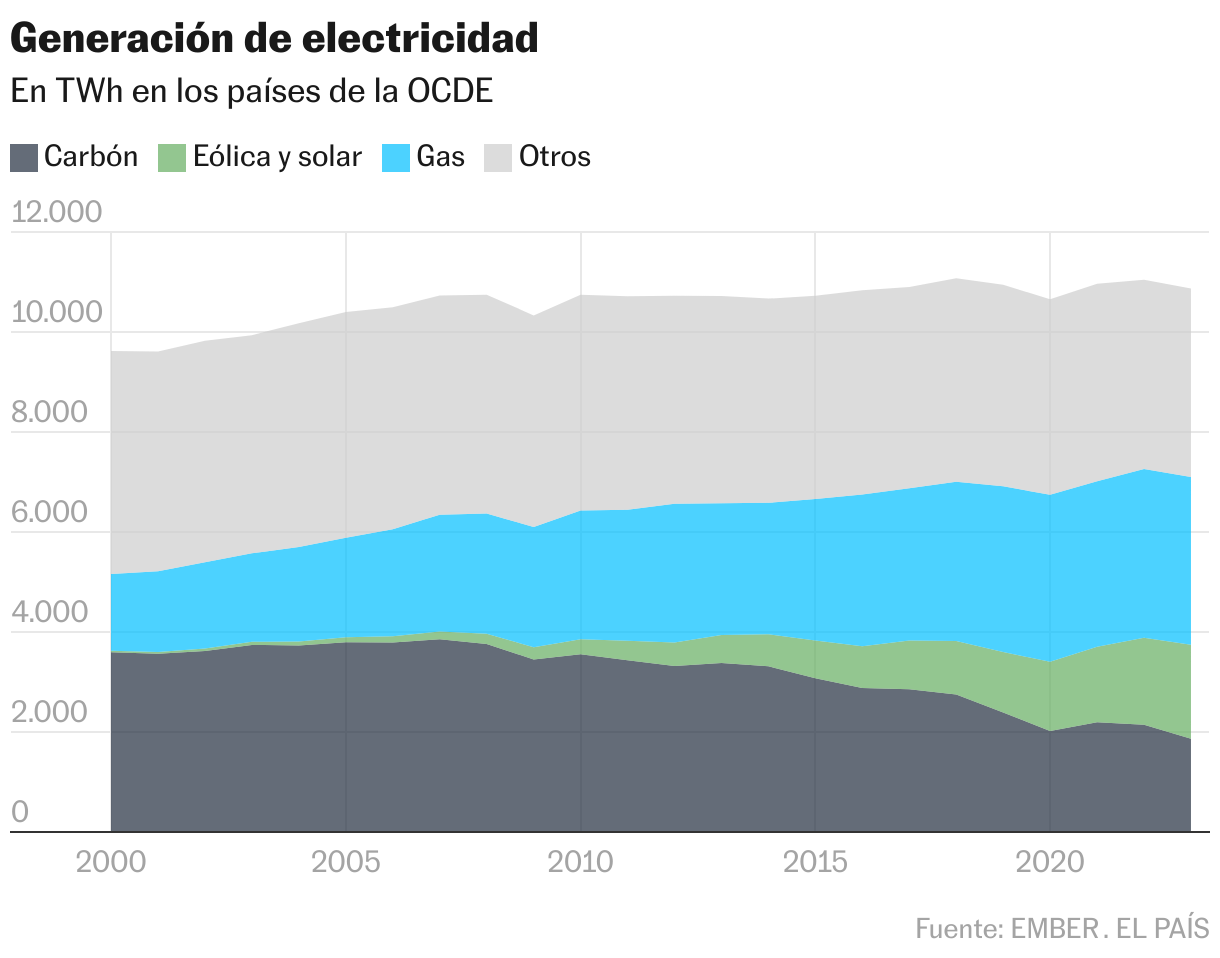

Evolution in the OECD

The closure of Ratcliffe-on-Soar is “part of a broader global trend,” says Ember, who points out that coal generation in OECD nations peaked in 2007. “And it has already fallen to half from that peak,” says Dave Jones, director of global perspectives for this organization. Coal currently accounts for just 17% of electricity generation in the 38 OECD countries, down from 36% in 2007. “The rapid growth of solar and wind energy was responsible for 87% of the fall in carbon during this period,” adds the Ember report.

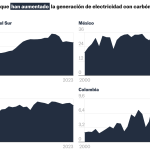

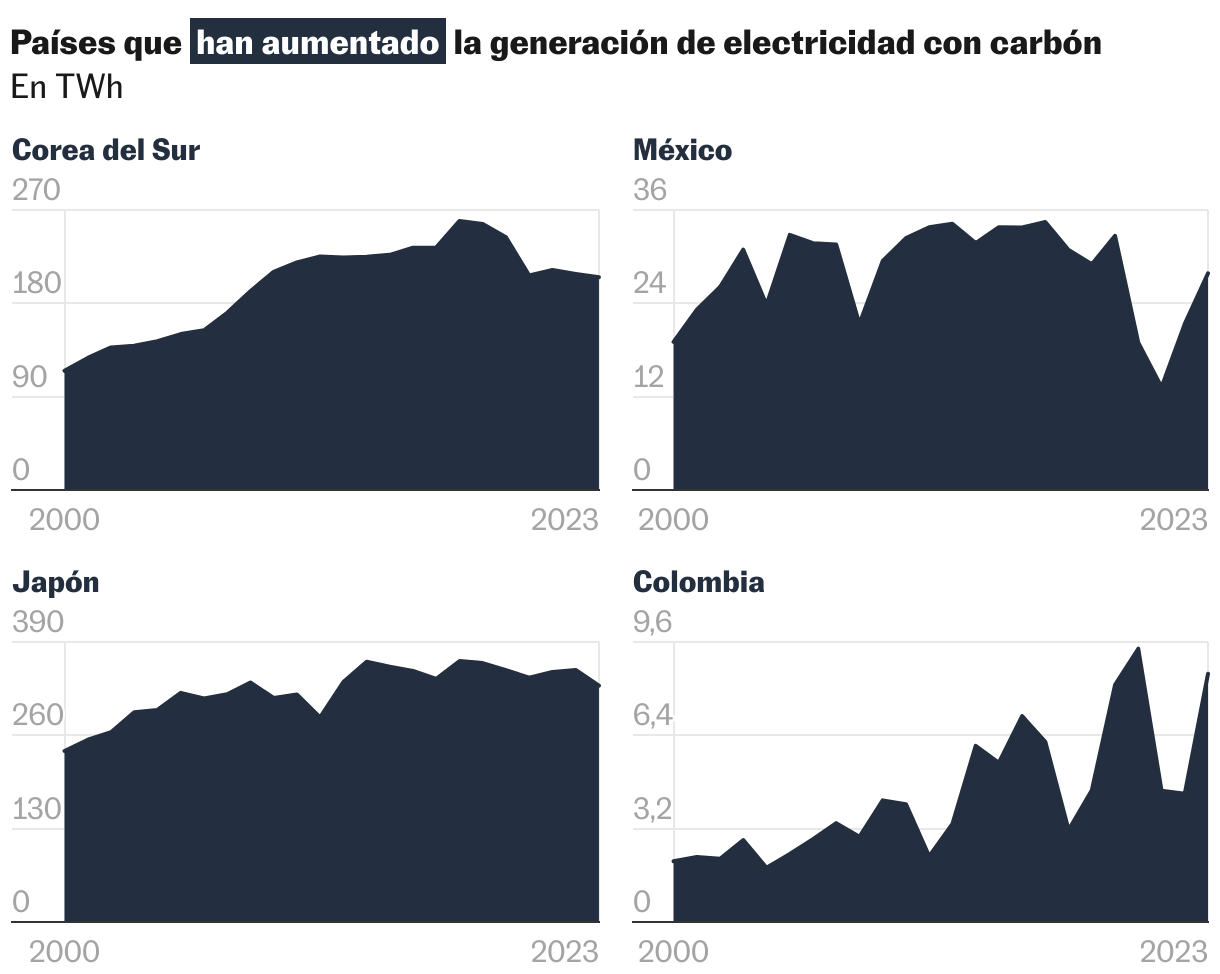

The concerns of international climate experts are now focused on some of the emerging countries where coal consumption continues to grow. The latest balance on this fuel from the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicated that in 2023 the demand for this fuel would fall again in almost all advanced economies, led by the EU and the US. However, this decline will be It would offset the growth expected for last year in China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Oxford Institute for Energy Studies researcher David Robinson is concerned about this “double speed”, although he adds: “it must be recognized that China is more than fulfilling its commitments on the penetration of renewables, electric vehicles, batteries and other relevant aspects for the fight against climate change.” In fact, this push for clean energy already caused a reduction in the use of coal in the Asian country at the beginning of 2024.

“China and India are far from standing idly by,” Jones insists. “In India, strong renewable energy targets for 2030 mean that most of the country’s growing electricity demand will come from renewables,” he adds.

Pending tasks in the United Kingdom

Beyond the end of the use of coal to generate electricity, the United Kingdom still has unfinished climate tasks. One of them is that the industries that continue to use this fuel (such as blast furnaces) stop using it. But, in addition, another fossil fuel is in the spotlight: natural gas. Although it emits much less carbon dioxide than coal, a third of the country’s electricity still comes from this fuel.

The new Minister for Energy Security and Climate Neutrality, Ed Miliband, has set the goal of achieving total clean electricity by 2030, for which gas must disappear from the system. It is a complicated task, because it means almost doubling the pace of acceleration promoted by previous conservative governments. But the idea of reinforcing the commitment with deadlines (which has worked with coal) has injected speed into other projects such as new generation wind plants or connections with Nordic Europe, to import part of the electricity that the island requires. .